Uranus might have toppled due to a missing moon, once 1/1000 its mass.

Key Takeaways

- Astronomers propose a large, ancient satellite of Uranus may have caused its extreme tilt.

- The gravitational interplay between the moon and Uranus could have gradually flipped the planet.

- Unlike Uranus, Neptune retained its satellites, including massive Triton, explaining its upright spin.

- A satellite migration rate similar to the Moon’s drift from Earth supports the new theory.

- More detailed data from future missions or JWST observations could confirm the hypothesis.

_______

Could a Lost Moon Explain Uranus’ Tilt?

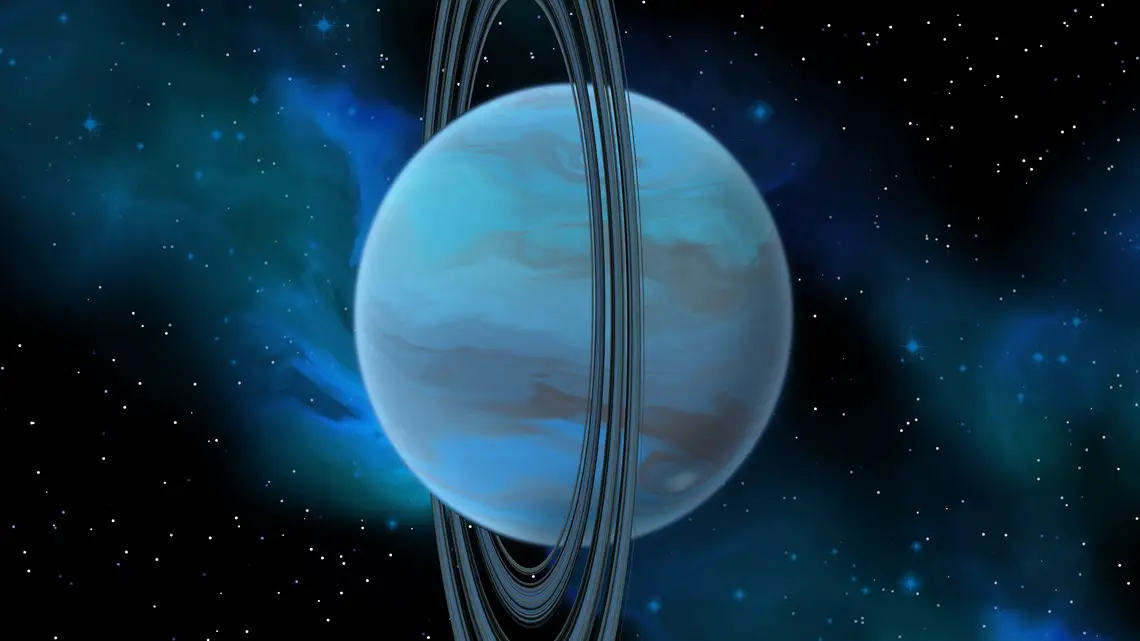

Uranus’ sideways spin, unlike any other planet in the solar system, has puzzled astronomers for decades. Conventional theories suggest a series of collisions tilted the planet, but this explanation falters when compared to Neptune, which shares a similar formation history yet spins upright. A new study led by Melaine Saillenfest of the Paris Observatory proposes an alternate explanation: Uranus was toppled by the gravitational influence of a large, ancient moon.

The theory hinges on the idea of tidal interactions, where a satellite’s orbital migration resonates with its planet’s spin axis. Simulations revealed that a moon just 1/1000th the mass of Uranus, drifting outward over a distance of 10 Uranus radii, could have gradually tipped the planet beyond 80 degrees. At this point, chaos ensued: the moon collided with Uranus, stabilizing its tilt at the current extreme angle.

This hypothesis explains why Uranus has no large satellite today, unlike Neptune, Jupiter, and Saturn, which boast moons like Triton, Ganymede, and Titan. The study, while compelling, acknowledges uncertainties, including whether Uranus could have hosted a moon large enough to cause such effects.

Future Observations Hold the Key

The research highlights the need for more data on Uranus’ current satellites, their migration rates, and other properties. Past missions like Galileo, Cassini, and Juno have provided vital insights into Jupiter and Saturn, but Uranus has only been visited once—by Voyager 2 in 1986.

Planned missions to Uranus remain on hold, leaving astronomers reliant on ground-based observations and the James Webb Space Telescope for new insights. Despite this limitation, Saillenfest’s model provides a robust starting point for future experiments, offering fresh avenues to explore the mysteries of Uranus’ unique spin.

Ref: Tilting Uranus via the migration of an ancient satellite: arxiv.org/abs/2209.10590