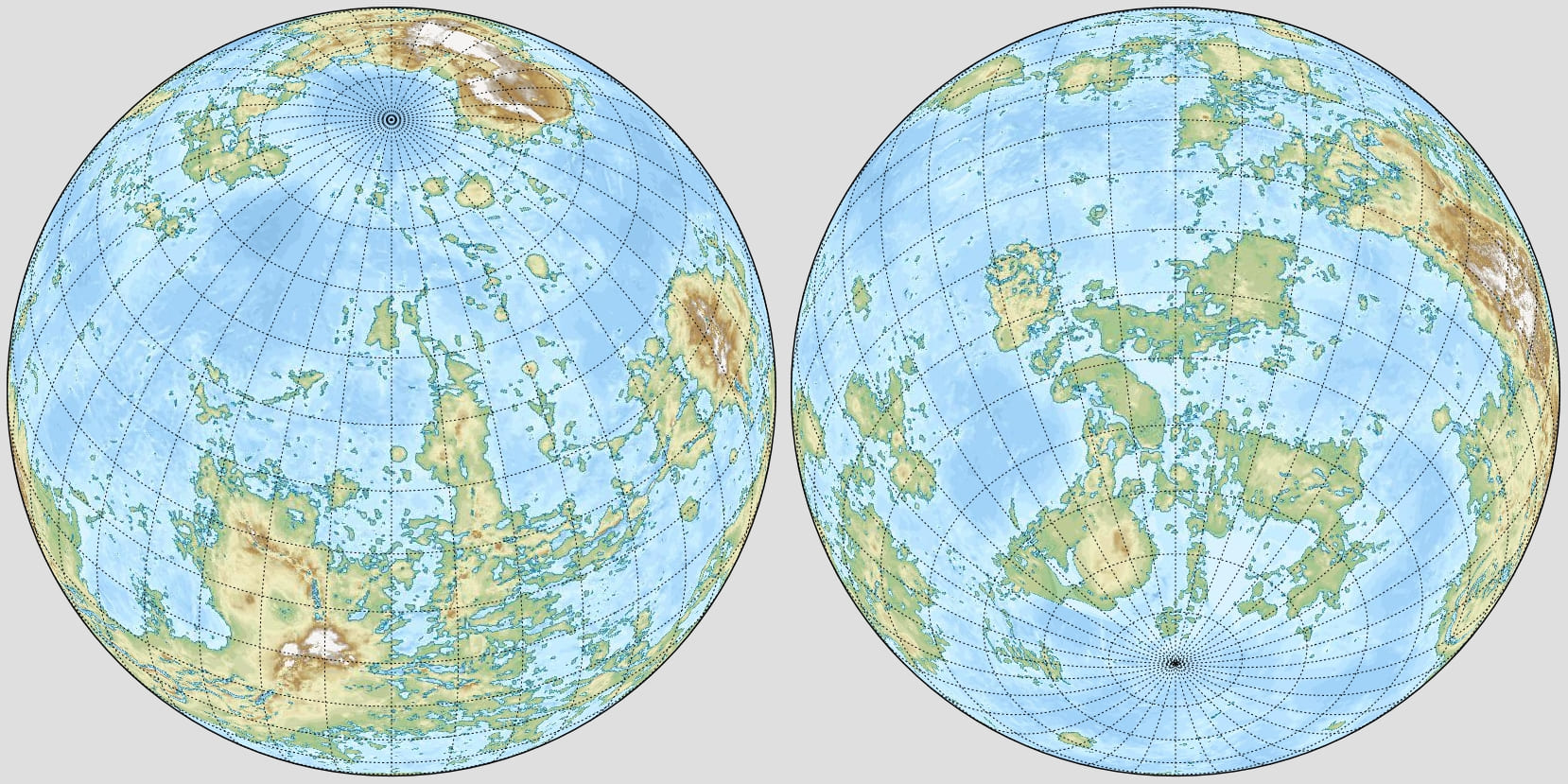

Venus’s Ishtar Terra, the size of Australia, would be its largest landmass as a water world.

Key Takeaways

- Venus as a water world would feature large continents like Ishtar Terra and Aphrodite Terra.

- The map by Alexis Huet uses Venus’s real topography, visualizing it with Earth-like oceans.

- Venus’s transformation into a water world would face challenges due to its extreme conditions.

- Terraforming Venus might be harder than Mars but has advantages like Earth-like gravity.

- The map inspires reflection on Venus’s past, its potential future, and humanity’s role in planetary habitability.

_______

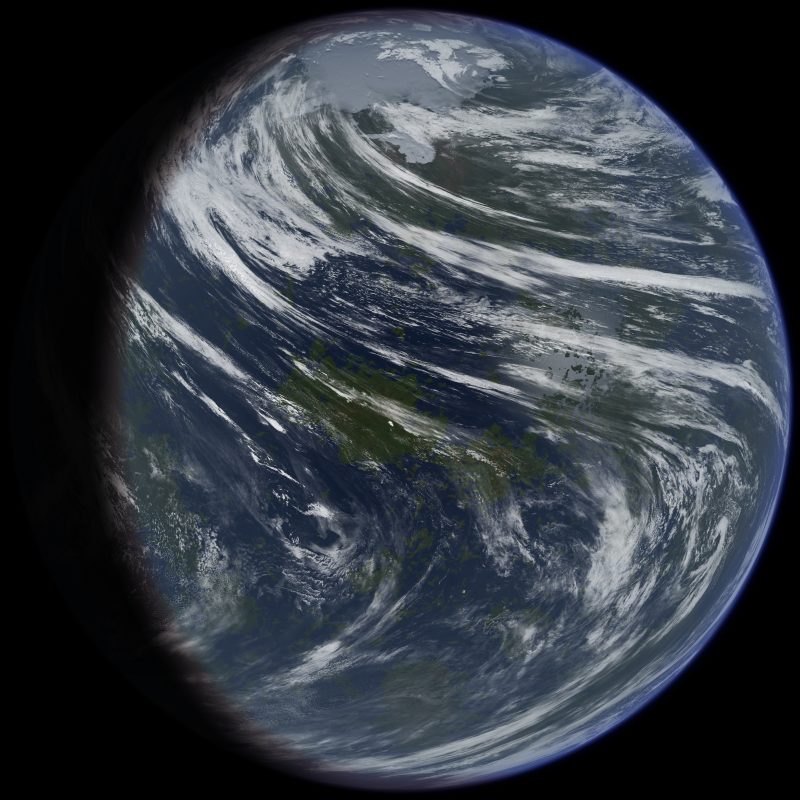

Reimagining Venus as a Water World

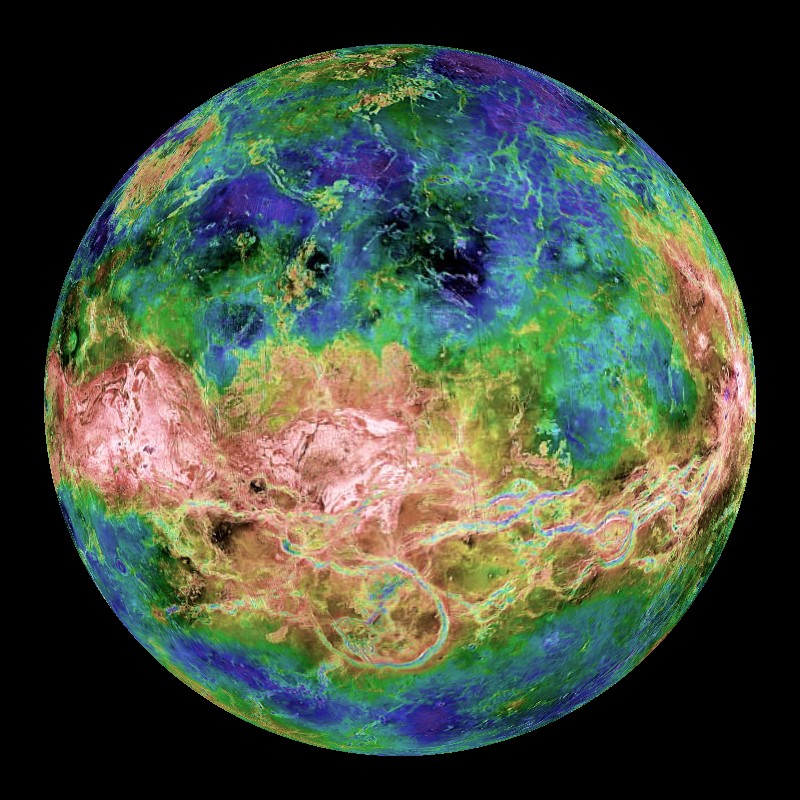

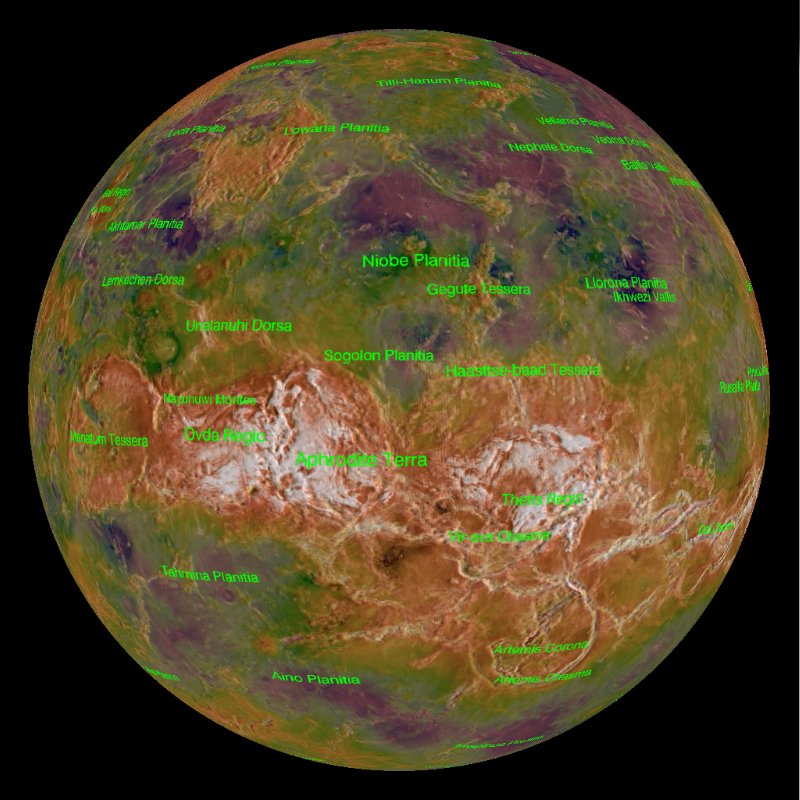

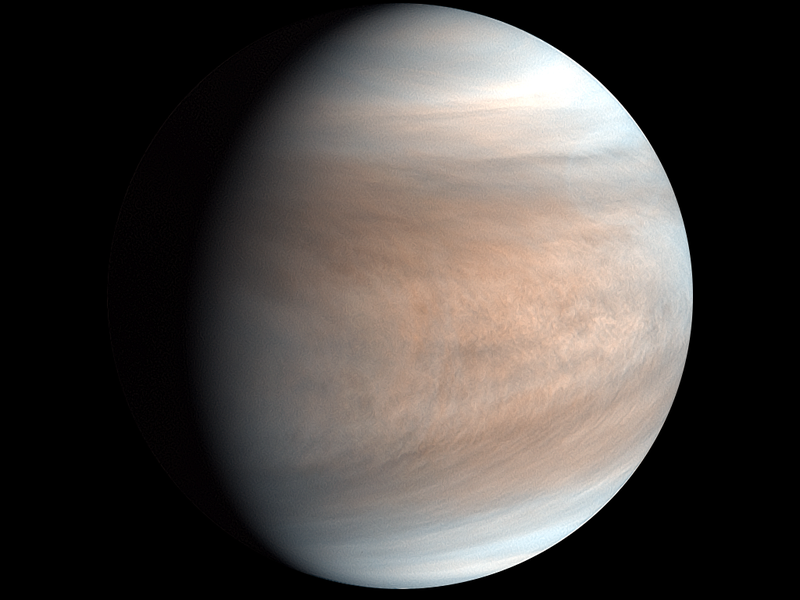

Venus, our neighboring planet, is one of the harshest environments in the solar system, with surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead and a toxic, crushing atmosphere of carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid. However, a viral map created by mathematician Alexis Huet imagines Venus as a water-covered world. Using Venus’s topography, the map portrays continents, islands, and oceans, offering a glimpse of what this planet might have looked like billions of years ago or could resemble in the distant future.

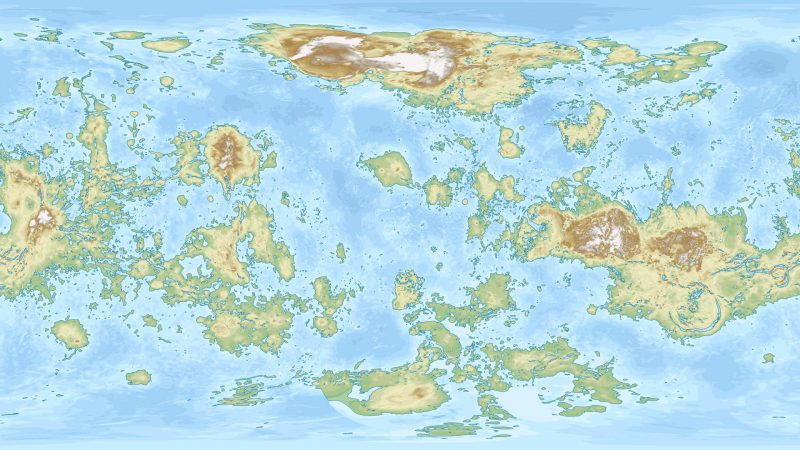

The map highlights two major continents on Venus. Ishtar Terra, located in the northern hemisphere, is comparable in size to Australia and contains Venus’s highest peak, Maxwell Montes. The equatorial region features Aphrodite Terra, a continent as large as South America stretched along the equator. Smaller islands and landforms scatter across the imagined oceans. While scientifically speculative, the map draws from radar data that penetrated Venus’s dense clouds to reveal its mountainous and flat regions.

The Science and Challenges of Terraforming Venus

Huet’s map represents an idealized vision rather than a realistic depiction. According to planetary scientist Paul Byrne, the surface shown lacks erosion and plate tectonics, which would shape continents differently if Venus had real oceans. Current Venus conditions make this scenario impossible; its extreme heat, pressure, and greenhouse effect prevent liquid water from existing.

Despite these challenges, scientists have long entertained ideas of terraforming Venus. Carl Sagan suggested seeding Venus’s clouds with algae in 1961, but the planet’s thick atmosphere rendered this unfeasible. Terraforming Venus would require reversing its runaway greenhouse effect by removing massive amounts of carbon dioxide, a colossal task needing advanced technology. However, Venus offers some advantages over Mars: it is similar to Earth in size and gravity, and cooling its atmosphere might be simpler than thickening Mars’s thin one.

While transforming Venus into a water world is far from achievable, the map fuels imagination about its past habitability and potential future. Scientists believe Venus may have hosted oceans billions of years ago before its climate became a hostile furnace. By considering these possibilities, we can better understand planetary evolution and explore ways to preserve Earth’s habitability.