Astronomers have recently uncovered a groundbreaking discovery: the oldest and most distant supermassive black hole known to science, residing within the quasar ULAS J1342+0928. This colossal black hole, reaching 800 million times the mass of our sun, existed just 690 million years after the Big Bang, placing it at a time when the universe was only 5% of its current age. Identifying such a massive black hole so early in the universe’s timeline has sparked significant interest among researchers, as it may provide critical insights into how black holes could have achieved enormous sizes so rapidly after the universe’s formation.

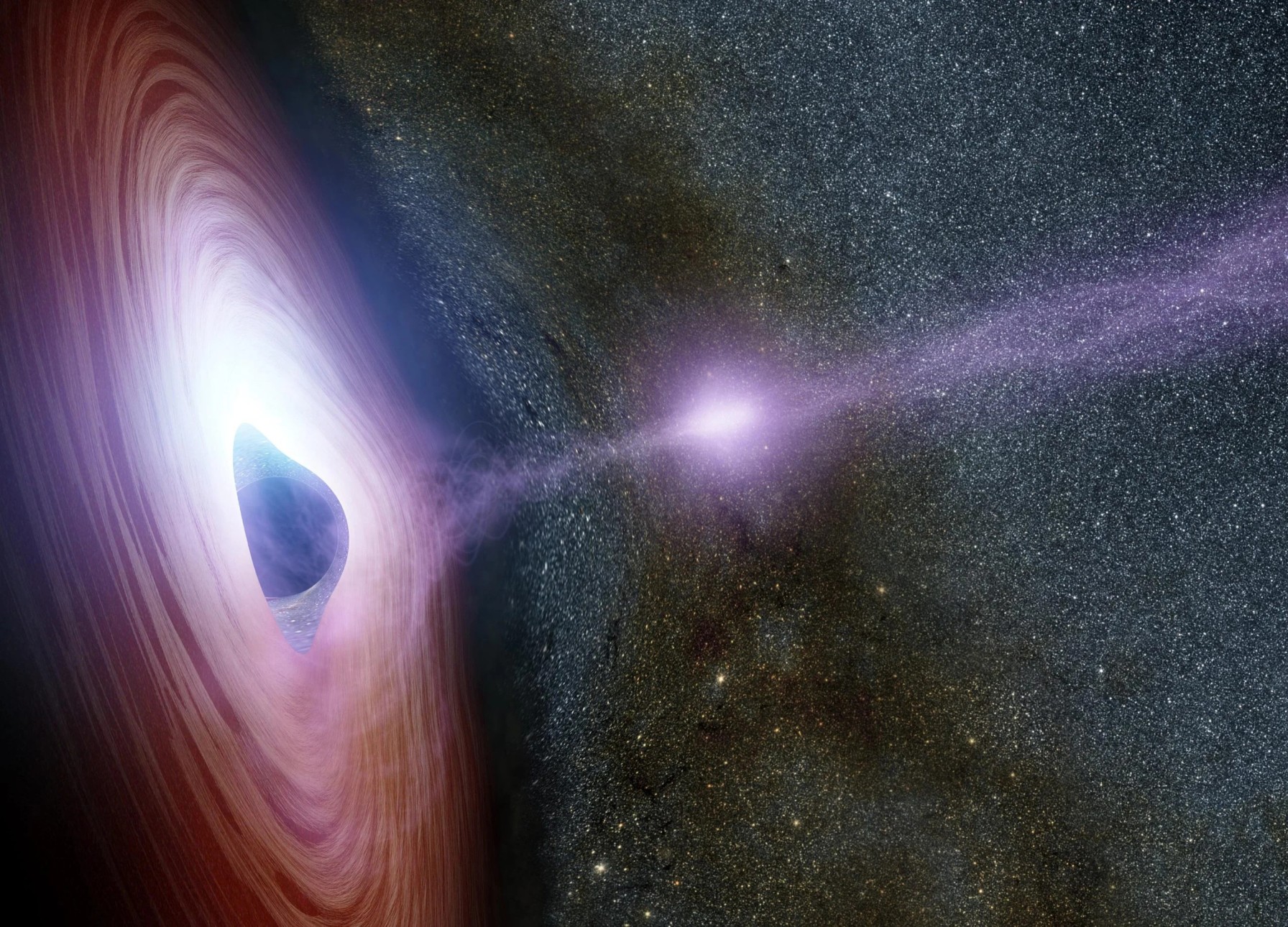

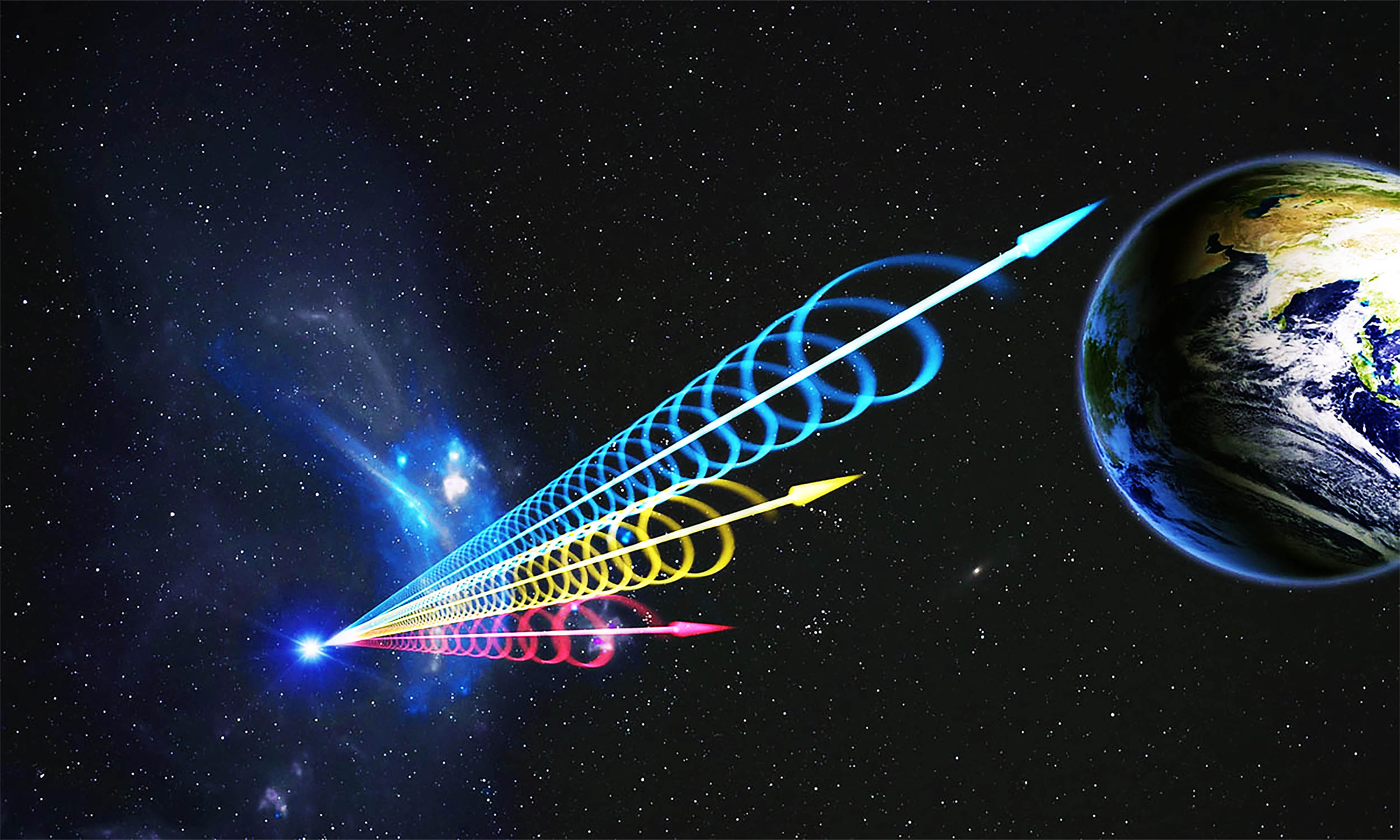

Supermassive black holes, each with millions or billions of times the sun’s mass, are thought to lie at the heart of nearly all galaxies. When they consume matter, they emit substantial light, powering quasars—some of the most luminous objects in the cosmos. These quasars are among the universe’s farthest known objects, as light from these ancient entities has taken billions of years to reach Earth. Before ULAS J1342+0928, the most distant quasar on record was ULAS J1120+0641, which existed 750 million years after the Big Bang, roughly 13.04 billion light-years away. By comparison, ULAS J1342+0928, 13.1 billion light-years from Earth, is an even earlier example of a supermassive black hole’s formation in cosmic history.

One of the most puzzling questions in astronomy is how black holes like the one in ULAS J1342+0928 could have accumulated so much mass so early. Eduardo Bañados, lead author of the study and an astrophysicist at the Carnegie Institution for Science, noted that quasars like ULAS J1342+0928 are extraordinarily rare and hold valuable information for understanding the growth mechanisms of supermassive black holes and their influence on the evolving universe. The team used several advanced telescopes, including the Magellan Telescopes in Chile and the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii, to observe the black hole, which offers a unique view into an era called the “epoch of reionization.”

Following the Big Bang, the universe was initially filled with neutral hydrogen, creating a dark, foggy cosmos. This state persisted until the first stars and galaxies began emitting powerful ultraviolet light, causing this hydrogen to ionize and gain an electric charge. This period, known as reionization, marks a pivotal transition in the universe’s history when light could travel freely, making the universe transparent. The newly discovered black hole lies within this epoch, providing essential clues to understand how and when the universe transitioned out of its “dark ages.”

The quasar’s surrounding hydrogen remains largely neutral, indicating that this black hole existed during the midpoint of reionization. This aspect could help astronomers pinpoint how this transformation took place and clarify whether stars or black holes were the primary drivers behind reionization.

Bañados emphasized the need for more such discoveries to deepen our understanding of early-universe phenomena. Despite the challenge, as these quasars are extremely scarce, their rarity and brightness offer a glimpse into the earliest epochs of cosmic evolution. Finding ULAS J1342+0928 signals hope that further exploration will reveal additional secrets about the rapid formation of black holes and the intricate history of our universe’s earliest days.

This is truly terrifying. It’s staggering to even try to comprehend 800 million times more massive than the sun…

Can someone please put this into context/scale for me? Maybe a nice handy graphic? I just can’t wrap my head around 800 million times

I feel like the universe should have a limit on mass.

What is shocking is how a blackhole can grow this fast in this little time. This is only several hundred million years after the big bang.

Just curious, is it possible for a black hole to eat every star in it’s Galaxy and become starless?

It’s bigger than comparing a grain of sand to the sun