35% of discovered planets might host vast oceans, some under extreme temperatures and pressures.

Key Takeaways

- Research suggests up to one-third of known planets could be massive water worlds.

- Super-Earths, planets several times Earth’s size, may consist of up to 50% water.

- Water worlds above 2.5 Earth radii likely resemble Neptune or Uranus, with hostile conditions.

- Life might exist in specific near-surface layers where pressure and temperature are favorable.

- The abundance of water underscores oxygen’s prevalence as the third most common element in the universe.

__________

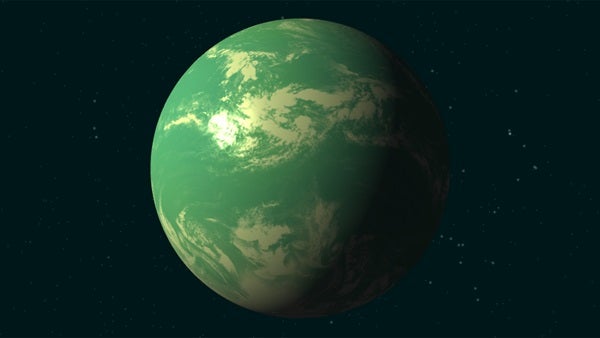

Recent research highlights the possibility that water-rich planets are widespread across the galaxy. Scientists analyzing super-Earths — rocky planets larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune — found many could consist of up to 50% water. By comparison, Earth’s water makes up only a tiny fraction of its mass.

These findings suggest that water, a critical ingredient for life, might be far more common than previously thought. Li Zeng, a Harvard researcher and the study’s lead author, emphasized that water is abundant in the universe due to the prevalence of oxygen, the third most common element after hydrogen and helium.

The study was presented at the Goldschmidt Conference, a leading event in geochemistry, and provides a new perspective on the composition and potential habitability of planets beyond our solar system.

Extreme Environments on Water Worlds

Not all water worlds would be habitable. Super-Earths with a radius under 1.5 times that of Earth are likely terrestrial and rocky. However, planets exceeding 2.5 Earth radii could resemble mini-Neptunes or Uranus-like worlds. These larger planets might have dense, water-vapor atmospheres and oceans subjected to intense temperatures (390–930°F or 200–500°C) and crushing pressures.

Despite these harsh conditions, Zeng posits that life could develop in specific layers near the surface if the pressure, temperature, and chemical environment are suitable. He also suggested that such planets may form similarly to gas giants, with a dense core beneath thick atmospheric layers.

The study’s models indicate that up to 35% of known exoplanets could be water worlds. This significant proportion raises new questions about planetary formation, the role of water in sustaining life, and the diversity of environments in the universe.

As scientists continue exploring these oceanic planets, future discoveries could revolutionize our understanding of habitability beyond Earth, opening the door to potential new forms of life and exotic ecosystems.

This article originally appeared on Discovermagazine.com.