Earth Might Have Had Rings Like Saturn, Leading to Craters and Ice Age During the Ordovician Period

TL;DR

Scientists suggest that during the Ordovician period, Earth may have had rings similar to Saturn’s, formed by debris from a broken asteroid. Over millions of years, this debris “rained” down on Earth, causing meteor impacts near the equator. The shadow of the rings might have also contributed to the Hirnantian glaciation, an intense global cooling period, leading to a mass extinction. This hypothesis adds new complexity to our understanding of how extraterrestrial events could have shaped Earth’s ancient climate.

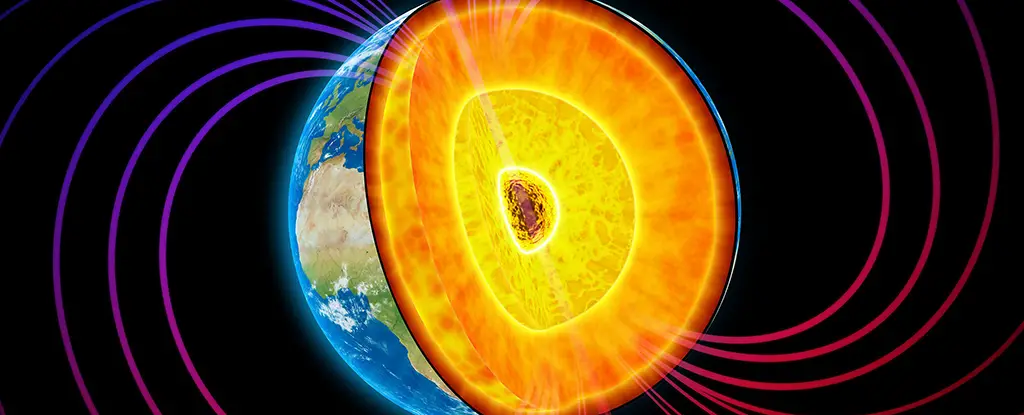

We’re all familiar with the appearance of Earth. Carl Sagan famously referred to it as the “pale blue dot.” It’s a small, rocky planet with a moon, a thin atmosphere, some land, and vast oceans.

However, Earth has gone through many transformations over its history. It’s been hot and fiery, extremely cold, and even without its moon. It was also in chaos after a massive collision with another space rock.

And—according to a study published recently in Earth and Planetary Science Letters—during the Ordovician period, Earth might have had rings. Yes, really.

The researchers developed this hypothesis by studying Earth’s ancient geology—specifically what it would have looked like during the Ordovician period through geological reconstructions. And what they discovered was unusual.

The research team identified 21 meteor impact craters from around 460 million years ago, all located within 30 degrees of the equator. This is particularly odd, as most of Earth’s land lies outside that narrow region, making it highly unusual to have so many impacts in one spot.

The most logical explanation for this, the researchers suggest, is that Earth once had a ring system that slowly dropped debris onto the planet. “Over millions of years,” said Andy Tomkins, the lead author of the study from Monash University, “material from this ring gradually fell to Earth, creating the spike in meteorite impacts observed in the geological record. We also see that layers in sedimentary rocks from this period contain extraordinary amounts of meteorite debris.”

Rings around planets can form in various ways, but the scientists believe Earth’s potential ring would have been created by the planet’s gravity pulling apart a nearby asteroid. This happens when an object, like an asteroid or moon, crosses into a planet’s Roche limit, where tidal forces overpower the object’s gravity, breaking it apart. The resulting debris can form a ring around the planet.

But such a ring wouldn’t last forever. The gravitational pull would continue, causing pieces of the ring to fall, or “rain,” onto the planet’s surface. Saturn’s rings, for example, are slowly “raining” out of orbit and are expected to disappear in around 100 million years.

This gradual ring “rain” could explain the craters. Since rings tend to form around equators, if Earth had rings and debris fell, we’d expect a pattern of equatorial impact craters like those found in this study.

And there’s more. “What makes this finding even more intriguing,” Tomkins noted, “is the potential climate implications of such a ring system.”

The period of these impacts coincides with the Hirnantian glaciation, also known as the Hirnantian Icehouse, a time of intense cold on Earth. This period saw glaciers form, sea levels drop, and a mass extinction event, the second largest in Earth’s history. According to the study, this was the coldest period in the past 540 million years.

The researchers suggest that the shadow cast by a ring system could have contributed to this intense global cooling. “The idea that a ring system could have influenced global temperatures,” Tomkins explained, “adds a new layer of complexity to our understanding of how extra-terrestrial events may have shaped Earth’s climate.”

Of course, this remains just a hypothesis. More research will be required to confirm these findings. Still, this study offers a fresh perspective on Earth’s history, potentially providing new insights into the planet’s past and helping us better understand the world we live in today.